PSYC2019OLIVEIRA42715 PSYC

An Evaluation of the Efficiency of Equivalence-Based Instruction

Type: Undergraduate

Author(s):

Juliana Oliveira

Psychology

Camille Roberts

Psychology

Advisor(s):

Anna Petursdottir

Psychology

Location: Session: 2; 1st Floor; Table Number: 3

View PresentationFew studies have directly evaluated the assumption that equivalence-based instruction establishes stimulus classes with greater efficiency than direct instruction of all possible stimulus relations within each class. Therefore, this study evaluated the efficiency of EBI protocol compared to direct instruction (DI), using fifteen visual abstract stimuli (A1 through E3). Forty-eight undergraduate students were assigned to one of four groups: The EBI-DI group received EBI in Phase 1 and DI in Phase 2, and vice versa for DI-EBI group. EBI-EBI and DI-DI group received EBI and DI in both phases, respectively. In Phase 1,EBI-first groups received training on AB and BC relations and DI-first groups received training with all possible relations. After achieving mastery criterion, the ABC test included all possible trial types. In Phase 2, all groups received training to (a) add a fourth stimulus (D), and (b) add a fifth stimulus (E) to the class. No statistically significant difference was found between EBI and DI-first groups in the number of trials, reaction time during test and overall trials to achieve criteria and the performance in ABC test. There was an interaction between the first training condition (EBI vs. DI) and the second training condition (EBI vs. DI) on percentage accuracy in the first ABCD test, but not in ABCDE test.

PSYC2019PAI44027 PSYC

Associations between Nostalgia and Attitudes towards Intimate Partner Violence

Type: Undergraduate

Author(s):

Anita Pai

Psychology

Cathy Cox

Psychology

Julie Swets

Psychology

Malia Yraguen

Psychology

Advisor(s):

Cathy Cox

Psychology

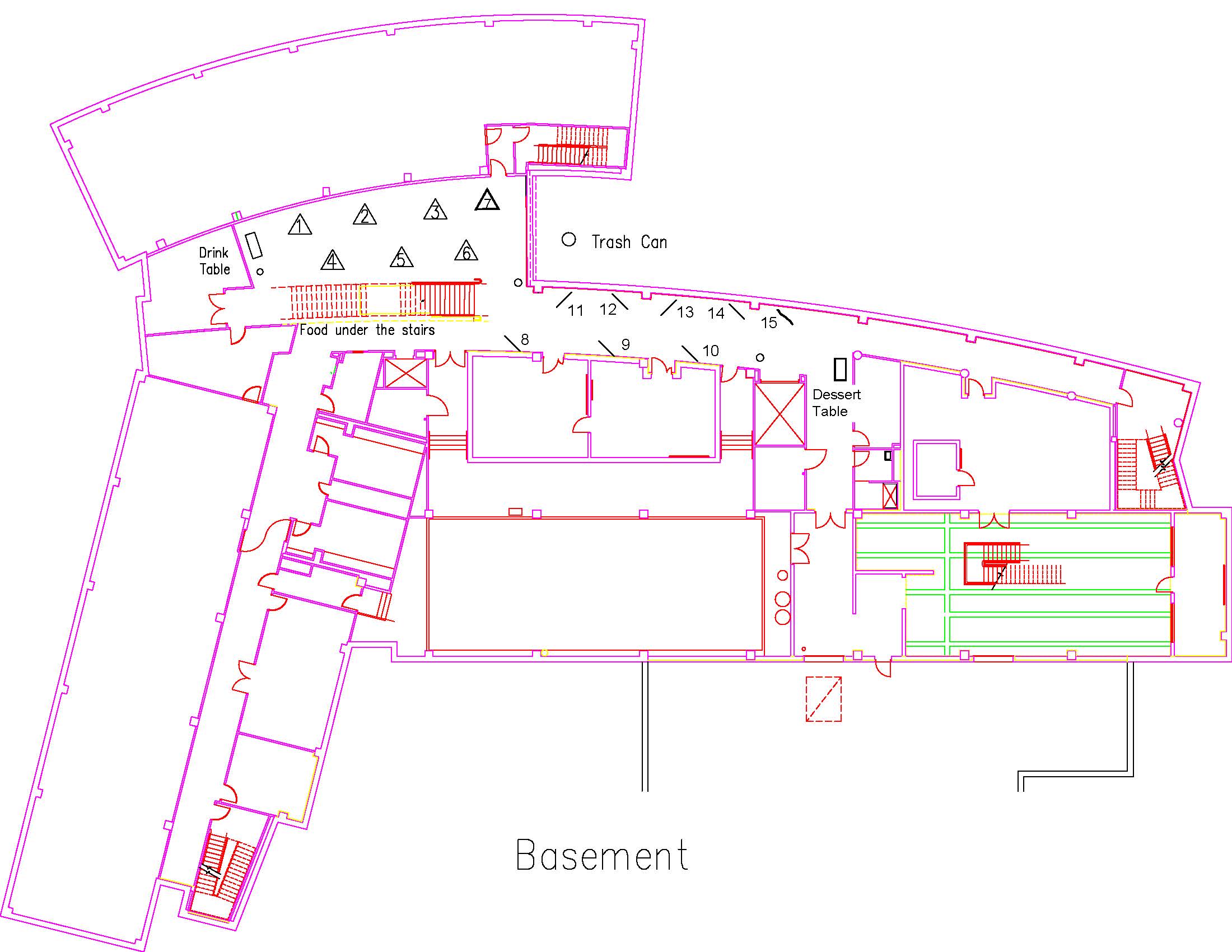

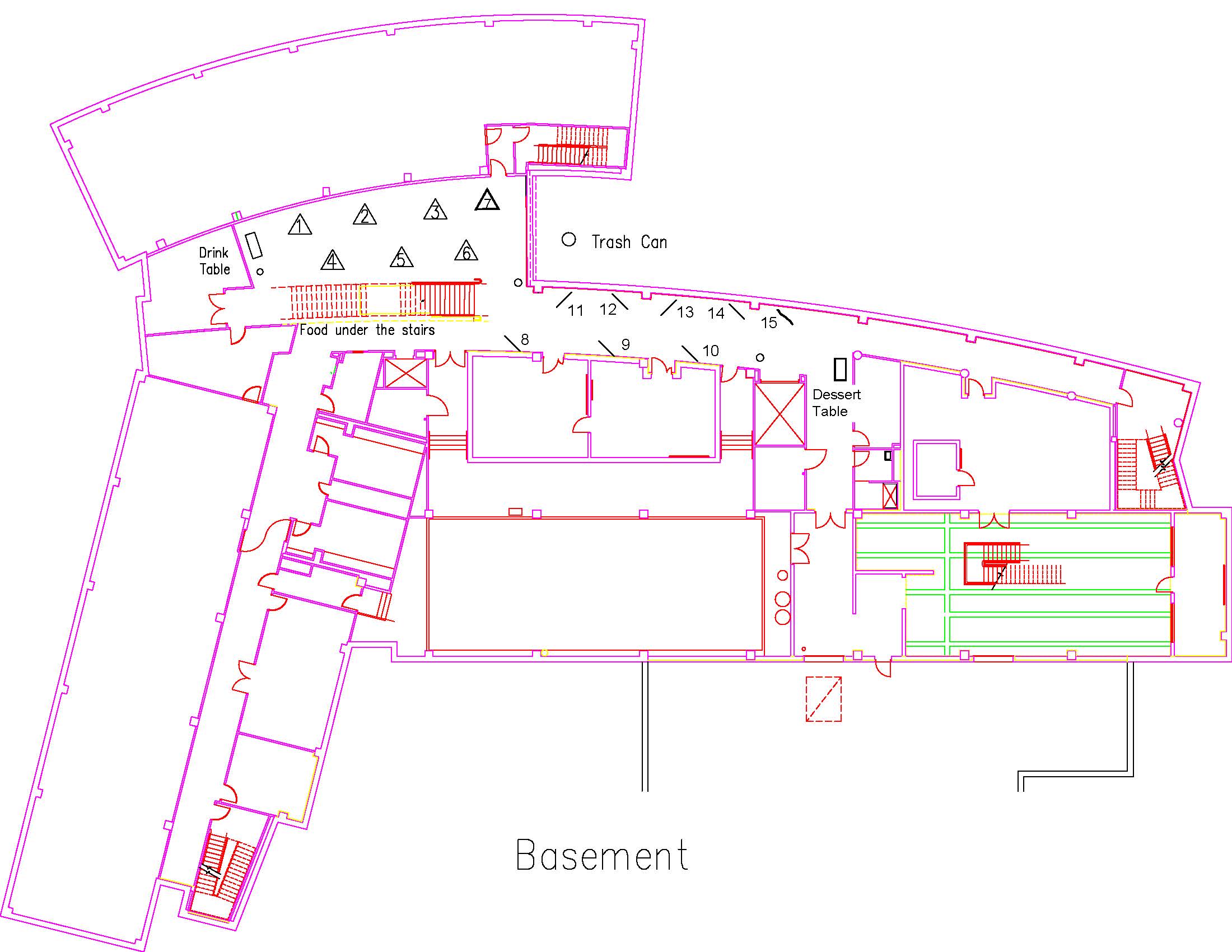

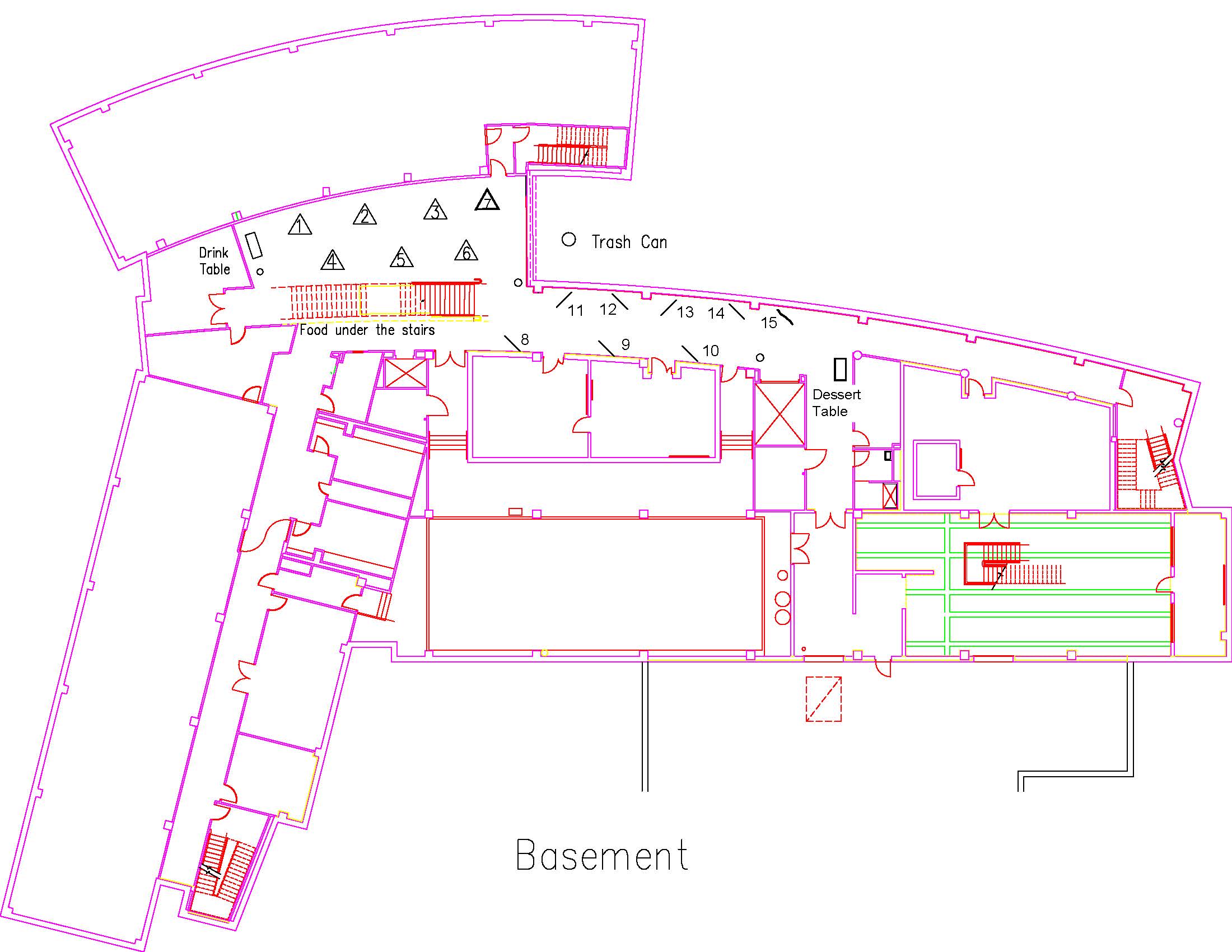

Location: Session: 1; Basement; Table Number: 6

View PresentationThis study explored the extent to which nostalgia proneness (a sentimental longing for the past) is associated with attitudes towards intimate partner violence (IPV). Research has found that individuals who report more conflict in their romantic relationships also report being more nostalgic for their own and for their relationships’ past. If nostalgia is related to more conflict in relationships, then it may also be related to greater acceptance of IPV. In this study, a sample of 142 participants completed measures of self-relevant nostalgia, relationship-relevant nostalgia, and attitudes toward IPV (using it and enduring it), and relationship outcomes (e.g., optimism, satisfaction, commitment). Results showed positive correlations between nostalgia (self-oriented and relationship-centered) and self-use of IPV (both using it and enduring it). These preliminary results suggest that a sentimental longing for the past is associated with endorsement of IPV use, however, other unexplored personality variables such as attachment style may moderate these associations. Future work should explore these findings in experimental and longitudinal designs.

PSYC2019PENN9049 PSYC

Regulation of Emotional Learning in Older Adults

Type: Undergraduate

Author(s):

Daniel Penn

Psychology

Paige Northern

Psychology

Amber Witherby

Psychology

Advisor(s):

Uma Tauber

Psychology

Location: Session: 2; Basement; Table Number: 12

View PresentationInvestigating how people regulate their learning is important because study decisions can impact actual learning. Compared to younger adults, older adults often show age-related deficits in memory. This deficit may be because older adults are less effective at regulating their learning. One factor that can influence memory is the valence of information. Prior research has established that older and younger adults are more likely to recall emotional information compared to neutral information and also predict that emotional information will be better remembered relative to neutral information (e.g., Tauber & Dunlosky, 2012). It is unclear how both age groups regulate their learning of emotional and neutral information. Investigating this issue, older and younger adults studied words that were positive (e.g., circus), negative (e.g., snake), or neutral (e.g., fork). Participants regulated their learning by self-pacing their study (Experiment 1) or by selecting half of the words to restudy (Experiment 2). After studying each word, participants predicted the likelihood of remembering it on a scale of 0% (will not remember) to 100% (will remember). Finally, participants took a free-recall test. Consistent with prior research, both age groups demonstrated higher predicted and actual memory for emotional information relative to neutral. Importantly, both age groups’ self-paced study times did not differ for emotional and neutral information. In contrast, both age groups restudied neutral words more frequently than emotional words. Thus, when participants were forced to strategize their learning, both age groups made good study decisions, prioritizing neutral information at the expense of emotional information.

PSYC2019PITCOCK43755 PSYC

Effect of Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation on Novel Letter Learning in Dyslexia

Type: Undergraduate

Author(s):

Madeline Pitcock

Psychology

Abby Engelhart

Psychology

Grace Pecoraro

Psychology

Zoe Richardson

Psychology

Vishal Thakkar

Psychology

Advisor(s):

Tracy Centanni

Psychology

Location: Session: 1; 2nd Floor; Table Number: 8

View PresentationFor my SERC grant proposal, I studied the effect of auricular vagus nerve stimulation (aVNS) on learning in adults with dyslexia. The vagus nerve is a cranial nerve that, when stimulated, initiates the release of two neurotransmitters (NT’s) that are important in learning and memory (norepinephrine and acetylcholine). When a stimulus is presented at the same time as vagus nerve stimulation, this increases neural plasticity for the paired item. We have already tested this approach on typically-developing adults using the auricular branch of the vagus nerve, which runs through the ear and can be stimulated non-invasively. During this intervention, timed bursts of electrical stimulation were delivered while the participant learned novel letter-to-sound correspondences for Hebrew letters with the goal of increasing recall and automaticity. We have already found significant improvements in letter recognition, reading speed, and nonword decoding in typically-reading participants receiving stimulation compared to those in control groups. Our ultimate goal is to help children with dyslexia read more fluently. In the first step towards this goal, we enrolled a group of adult participants with dyslexia who received 10 days of Hebrew orthography training paired with aVNS. Participants were evaluated at four timepoints to monitor learning and compare progress with other groups: at day 1, halfway through training, at the end of training, and 3 weeks after training ended. We measured letter recognition, letter-to-sound fluency, and decoding at each time point. We will present our preliminary findings at SRS and discuss future directions.

PSYC2019SHORT15670 PSYC

Early Life Environmental Factors, Impulsivity, and Inflammation in Children

Type: Undergraduate

Author(s):

Tori Short

Psychology

Jeffrey Gassen

Psychology

Sarah Hill

Psychology

Summer Mengelkoch

Psychology

Advisor(s):

Sarah Hill

Psychology

Location: Session: 1; Basement; Table Number: 11

View PresentationEarly life stress has shown to be related to an increased preference for smaller, more quickly acquired rewards over larger, delayed rewards—or an inability to delay gratification—a fundamental component of impulsivity. Beyond this, impulsivity is also characterized by difficulty concentrating and exercising self-control and has been found to significantly impact learning and memory. Specifically, in children, higher impulsivity is associated with greater learning difficulties, such as with reading. Previous research has also shown that adults with higher levels of inflammation portray higher impulsivity. The current study aims to investigate the relationship between impulsivity, inflammation, and childhood environmental conditions within children between the ages of 3-17. Saliva samples were collected from 248 children visiting the Fort Worth Museum of Science and History in order to measure current levels of proinflammatory cytokines, which indicate immune activation. Children then participated in a series of tasks that measured their ability to concentrate, learn to inhibit their responses, and delay gratification, while background and demographic information was collected from their parents. Results will reveal whether children growing up in stressful environments also have higher levels of inflammation and impulsivity.